58 E L EC TR I C AL CONNEC T I ON

AU T UMN 20 1 7

VRLA batteries are prominent, but

so are lithium batteries because of

their high ratios of energy to weight.

More varied than for lead-acid types,

the chemistry for lithium batteries is

outlined below:

The cathode in such batteries is a

lithiated metal oxide, and the anode

is made of graphitic carbon with a

layered structure. The electrolyte is

made up of lithium salts dissolved in

organic carbonates.

When the battery is being charged,

lithium atoms in the cathode become

ions and migrate through the

electrolyte towards the carbon anode

where they combine with external

electrons and are deposited between

carbon layers as lithium atoms. The

process is reversed during discharge.

In outline, efficiency is close to 100%

and life span approaches 3000 cycles

at 80% depth of discharge. Operating

temperature ranges from –30ºC to

60ºC, energy density is 90-190Wh/

kg and self-discharge is about 1% per

month. However, the higher cost is due

to special packaging needs and internal

over-charge protection.

On the basis of amp-hour ratings, the

cost comparison with VRLA batteries is

unfavourable. Yet when depth of discharge

is considered the picture changes.

It is generally accepted that the

most economic and practical DOD for a

VRLA-AGM battery is 50%. For lithium-

iron-phosphate (LiFePO4 or LFP) – the

safest of the mainstream Li-ion battery

types – 80% DOD is used.

CHARGING

The main aim in charging lithium

batteries is temperature control to

minimise the effect of lithium plating of

the anode.

Much depends on the physical

design. A thin, highly porous anode

works best for very fast charging –

rates as high as 1C.

Undercharged lithium batteries

lose capacity permanently, requiring

special precautions on recharge

circuits. Lithium-ion batteries cannot

absorb overcharge. When they are

fully charged, the charge current must

be cut off. A continuous trickle charge

would cause plating of metallic lithium

and would compromise safety.

Over time, the open circuit voltage

will settle to between 3.70V and 3.90V

per cell. A typical charge profile for a

single cell is shown in Figure 7.

For a partly discharged cell, a pre-

charge precedes the transition to

constant current charging. Monitoring

of cell voltage is essential, in order to

switch over at the correct voltage to

constant voltage charging.

When dealing with battery packs,

equalisation of voltage between the

cells is very important.

Unlike lead acid batteries, which can

equalise simply through out-gassing,

there is no natural equalisation

mechanism for lithium batteries.

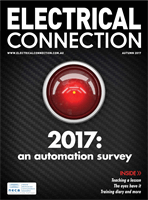

Their employment in strings and

parallel strings requires that unequal

cell voltages be eliminated. Methods for

achieving this include flying capacitor

circuits and many others. The flying

capacitor circuit is illustrated in Figure 8.

Capacitors constantly switch between

cells, thereby swapping charge from

higher-charged cells to lower-charged

cells. Each capacitor requires simple

controls to activate the switches.

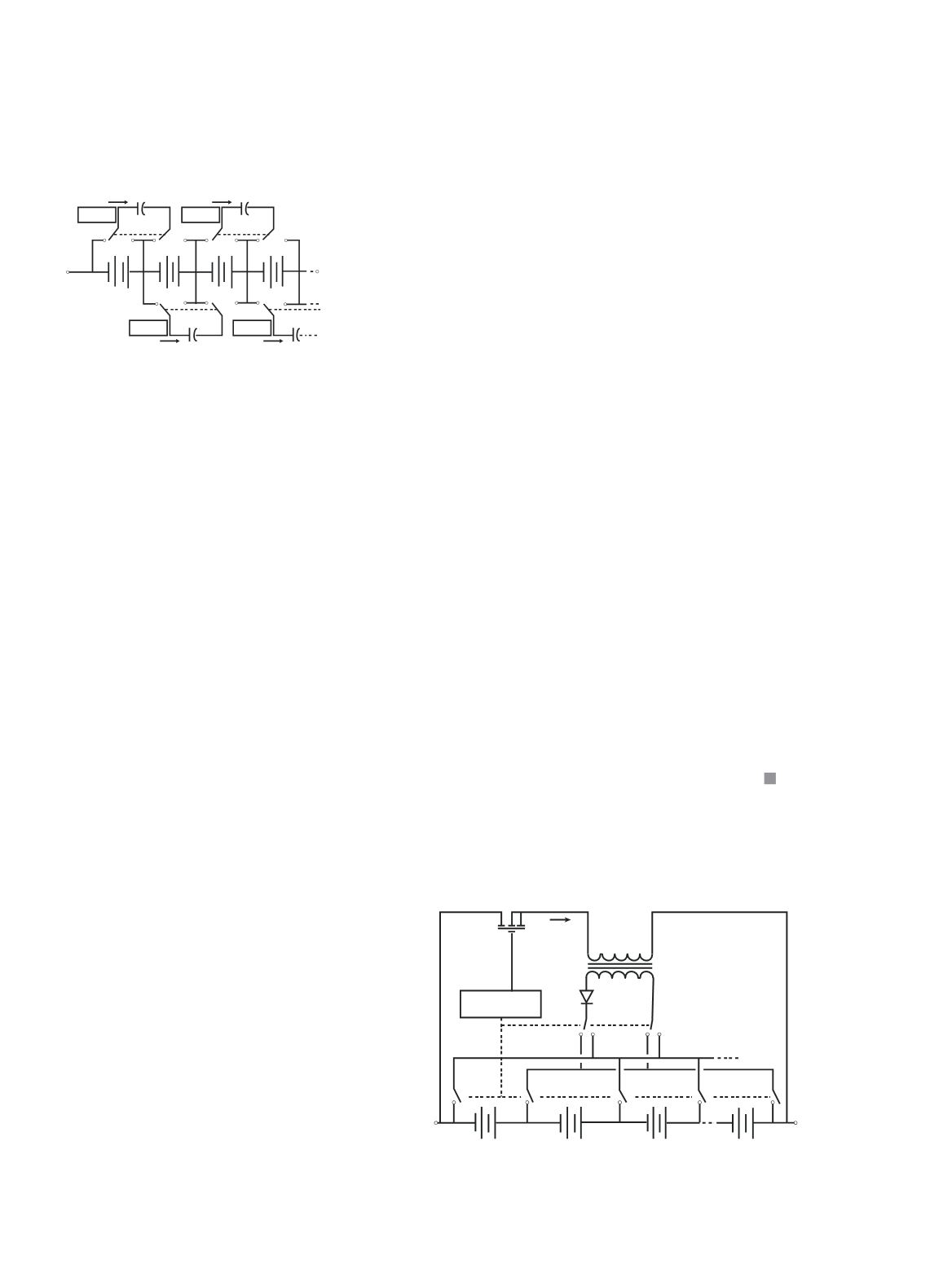

There are other methods, such as the

switched transformer method.

Figure 9 shows the stack voltage

being chopped by the transistor-control

circuit, which also monitors individual

cells, and the rectified voltage from

the transformer secondary replenishes

individual cells.

As will be evident, the voltage

equalisation circuitry as described

can form the basis of a battery

monitoring system. This has been

used, possibly experimentally, in some

commercial vehicles.

Control

3 3

I

3

B

3

B

C

4 4

I C

Control

Control

1 1

I

1

B

2

B

C

2 2

I C

Control

Figure 8: Voltage equalisation with flying

capacitor circuit.

n+1

S

4

S

3

S

2

S

1

S

D

T

n:1

I

1

B

2

B

3

B

n

B

Control

Figure 9: Switched transformer voltage equalisation.