www. e l e c t r i c a l c o n n e c t i o n . c om . a u

57

powered by potential and current

transformers. However, many are now

electronic, using microprocessors and

requiring a constant DC power supply

– or at least as an alternative if the

normal energising is via a switch mode

power supply.

Although we are focusing on

batteries, charger functions should

also be checked. The challenge in

the above arrangement is to provide

stable voltage under normal operation

and appropriate voltage for the float

charging process.

Furthermore, account must be taken

of operating with parallel battery

strings, and protection – for example,

ensuring that one battery’s shorting

does not affect the others.

A very important parameter in

chargers is ripple. The AC ripple sitting

on top of the DC current component is

deleterious to batteries. It may not be

an intuitive reaction if one looks at a

sine wave about a DC level. There are

as many peaks going higher than the DC

value as there are troughs below.

That might lead you to conclude that

the net result is simply the effect of the

DC component only. However this is not

the case. The actual rms (heating value)

is given by the formula:

In the formula, I

eff

is the effective

charging current, I

DC

is the DC

component, and I

AC

, the AC component.

In substation maintenance,

testing ripple is crucial. If the voltage

ripple is sufficiently large during

negative excursions to be under the

open circuit cell voltage, discharges

will take place.

The current ripple component

provides additional heating. For

minimal heating influence on the

battery banks, ripple voltage should be

well under 2% peak to peak, and under

4% peak to peak if discharge effects are

to be avoided.

Although DC circuits in substations

vary widely, there are several aspects

that must be taken account of. The first

one being protection against battery

cell shorts.

The principle of the circuit is shown

in Figure 5, in which two parallel

strings are shown by way of example.

The circuit would also apply to a large

number of parallel strings.

The underlying assumption is that,

apart from forward voltage drops in

the steering diodes, the load and the

batteries can use the same voltage. Yet

that is often not the case.

If a battery cell or cells shorts in the

second string then diode D3 will be

reverse biased. Charging of the string

can still take place via D4, but

no current can be drawn from the

first string.

In many applications, a float charge

service is required whilst supplying

the critical load during normal

operation. In this instance charging

current must be limited. The circuit

shown in Figure 6 fulfils this function

by means of a current-limiting resistor.

The battery string discharges via the

diode when main power fails.

Substation power supplies

incorporating charging functions can

be provided with a number of

important features, including high and

low voltage alarms, AC and DC output

status, ripple alarm and battery ground

detection for floating DC supplies.

A battery ground-detection system

uses a resistive voltage divider so that

positive and negative terminals of the

battery bank maintain equal magnitude

voltage values with respect to ground.

The resistive divider has an added

benefit, namely to function as a

bleed-off for any capacitively coupled

voltages that might interfere with the

operation of protective relays.

As a further improvement, battery

monitoring can be installed. This is

generally based on measuring two

important parameters: cell voltage

and impedance.

One method involves the injection

of a very small high-frequency current

and measurement of the voltage drop

across the cell. Battery impedance

coupled with open circuit cell voltage

provides a very good ‘state of health’

for batteries.

TRACTION

Smaller vehicles are the focus here,

including forklifts, ground equipment

for airports, and short-range transport.

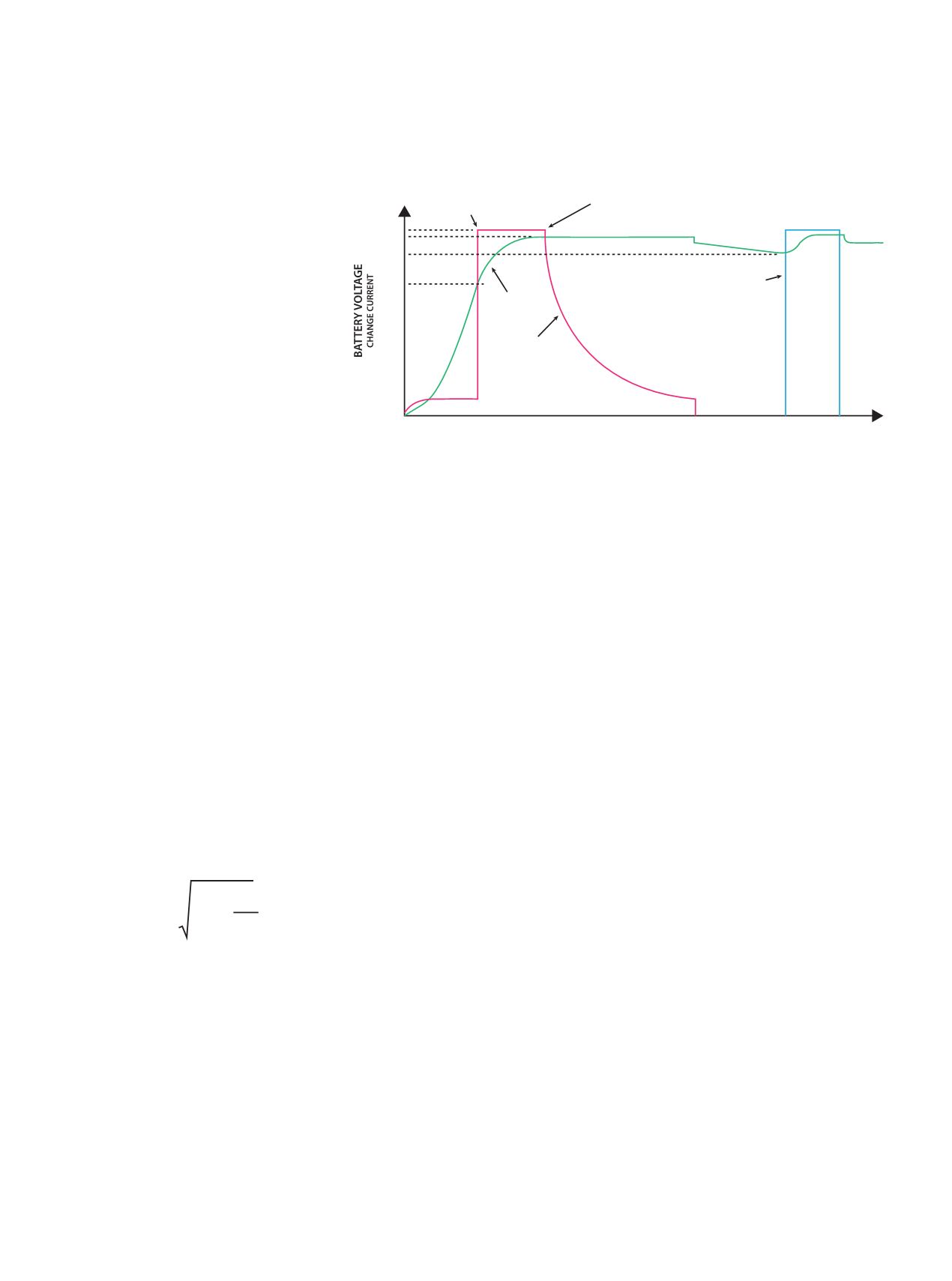

CC to CV transition

4.1 (Default)

Proqualification to Fast

ChargeTransition

1C

3V

4.1V

3.9V

0.1C

Battery

Voltage

Battery

Current

End of Charge

Current

0.1C (Default)

Charge

maintenance

pulse

TIME

I

I

2

= +

eff

2

DC

I

2

AC

Figure 7: Charging profile for a Li-ion cell.