56 E L EC TR I C AL CONNEC T I ON

AU T UMN 20 1 7

shorten battery life in the long term.

Charging current Ic is equal to the

difference in charger voltage and cell

voltage divided by the total resistance,

which takes into account any current-

regulating resistance, circuit resistance

and cell internal resistance.

The higher the charging rate, the more

quickly cell voltage rises, necessitating a

further increase in charging current and

a rise in cell temperature.

Figure 3 shows the process for a 5C

charging rate, that is, a 200A-h battery

would be bulk charged initially at 40A.

As the graphs show, temperature rises

slowly initially but then takes on an

exponential slope. It is clear that to

prevent excessive temperature the

rate of charge should be decreased as

the battery approaches 80% charge.

BATTERY CHARGERS

Before looking at substation DC

power reticulation, charging circuits

should be examined.

A constant voltage charger should

in the first place have an output

above the highest open circuit cell

voltage. It has the advantage that

current decreases as the battery

gains charge, but its charging rate will

be considerably slower than with a

constant current source.

However, such a charger should have

a way of stepping the charger current

down as the battery gains charge.

For substation duty some form of

charger temperature compensation

is important. This also applies to the

battery bank room, which ideally should

be held within a tight band of 15-25°C.

Temperature has a substantial

effect on float current provided by

a constant voltage source. The float

current must roughly double for each

10°C rise in cell temperature.

Increased heating of cells and

reduced heat flow from batteries

increases the risk of thermal runaway.

Higher ambient temperatures are

obviously implicated here.

This effect is particularly observed

in VRLA batteries rather than in

vented (flooded) cells, because the

formation of oxygen is an exothermic

reaction. In the case of sealed VRLA

batteries, the heating effect and joule

losses can add up very quickly to

higher temperatures.

The ability to de-sulphate the

negative plate, which gains a layer

of lead sulphate as the battery

discharges, is an advantage. Some

chargers incorporate a de-sulphating

pulse, although its mechanism is not

well understood, and some chargers

use a form of pulse width modulation

to control the charging process.

This latter method combines the

advantage of constant current

charging with the inbuilt feature

of tapering current of constant

voltage chargers. Using pulse width

modulation, the current pulse width

is reduced by means of an algorithm

and/or a suitable feedback mechanism

based on cell voltage.

DC CIRCUITS

Substation DC circuits vary, but

there are some generalities as shown

in Figure 4.

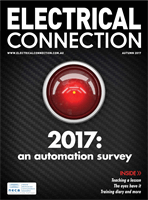

In the dual-battery system as shown,

the chargers A and B function not only

to trickle charge the two banks but

also to supply the various DC circuits:

that is, DC coils for circuit breakers, DC

motors for energising trip springs, and

protection relays.

Electro-mechanical versions are

D1

+

+

+

+

-

-

D2

Ba

Fa

Fb

Bb

D3

D4

Load

Charger or

Rectifier

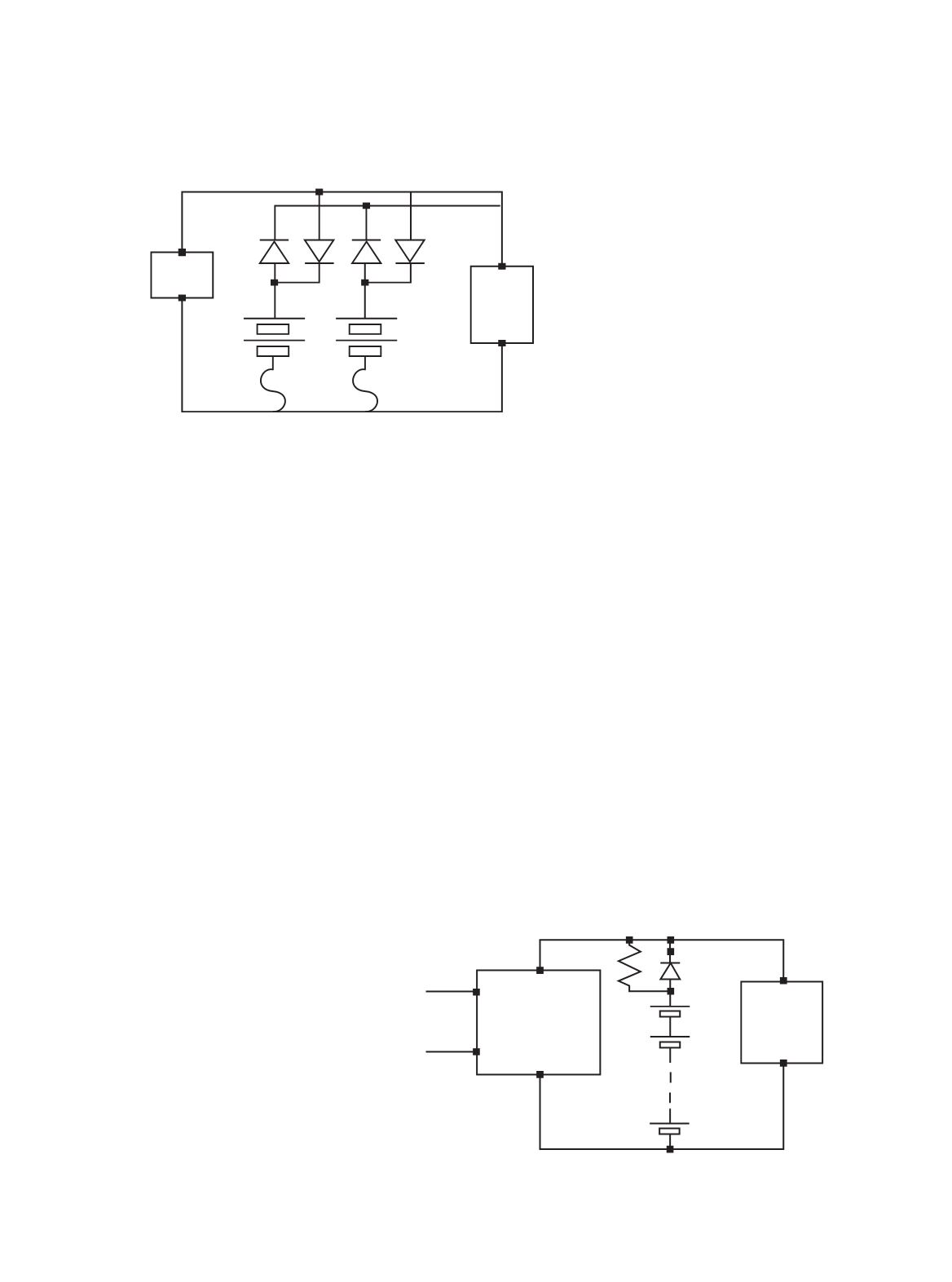

54 DC

Power Supply

and Battery

Charger

C1

C2

C24

Rc

D

+

+

+

24 Cell

48 VDC

Battery

Commercial

AC Power

Input

Critical

Load

Figure 5: Protection of parallel strings.

Figure 6: Parallel supply of load and float charge.