38 E L EC TR I C AL CONNEC T I ON

AU T UMN 20 1 7

LED BY EFFICIENCY

W

e live in a 24/7 world, in

which artificial lighting

represents a huge part of

humanity’s energy use.

Electric lighting is mainly provided

by alternating current (AC) with direct

current (DC) being sourced from

batteries and solar panels.

In Australia and elsewhere in the

‘first world’, the development path

has been to higher-efficiency

lighting, with light-emitting diodes

(LEDs) leading the way in energy

conservation. The luminous efficiency

of LEDs far surpasses other

technologies and drawbacks such as

colour and small angular dispersion

have been overcome.

However, we are not taking full

advantage of the technology. We

could be availing ourselves of more DC

energy than is commercially on offer.

There are substantial efficiencies to be

gained by using DC rather than AC as

primary input.

This article looks at short-term

and long-term developments in the

energising of LEDs and takes a brief

peek at a world in which much AC low-

voltage reticulation is being replaced

by DC.

DC is already being used with

USB-powered LED strings – clearly a

hobbyist’s venture but nevertheless an

indication of things to come.

LED illumination products have

become so well established in a

relatively short time that the basic

understanding of circuits and physical

properties now seems unimportant. Yet

these basics provide further insight into

development opportunities for custom

lighting designers and experimenters.

A BRIEF TOUR OF LEDS

The light-emitting diode is in many

ways barely a diode.

It quickly exhibits avalanche

breakdown under reverse polarities

of 5V reverse bias or more, therefore

requiring protection against such

events by means of clamping diodes.

The basic operation in the forward

direction is like that of any semi-

conductor diode. By increasing the

positive voltage in the P (acceptor)

region, electrons from the N (donor

region) are encouraged to flow to the

P region.

In LEDs electrons lose energy as

they jump back from the conduction

band to the ‘valence’, or bound region

(where they form part of the bonding

links between neighbouring atoms).

This energy is emitted in the form of

light quanta.

LEDs are therefore very similar to

photovoltaic cells, in which the

reverse process takes place. However,

the photovoltaic effect can also

happen in LEDs. In fact, it can be

used for testing LED wafers, thereby

avoiding damage to delicate copper

conduction terminals.

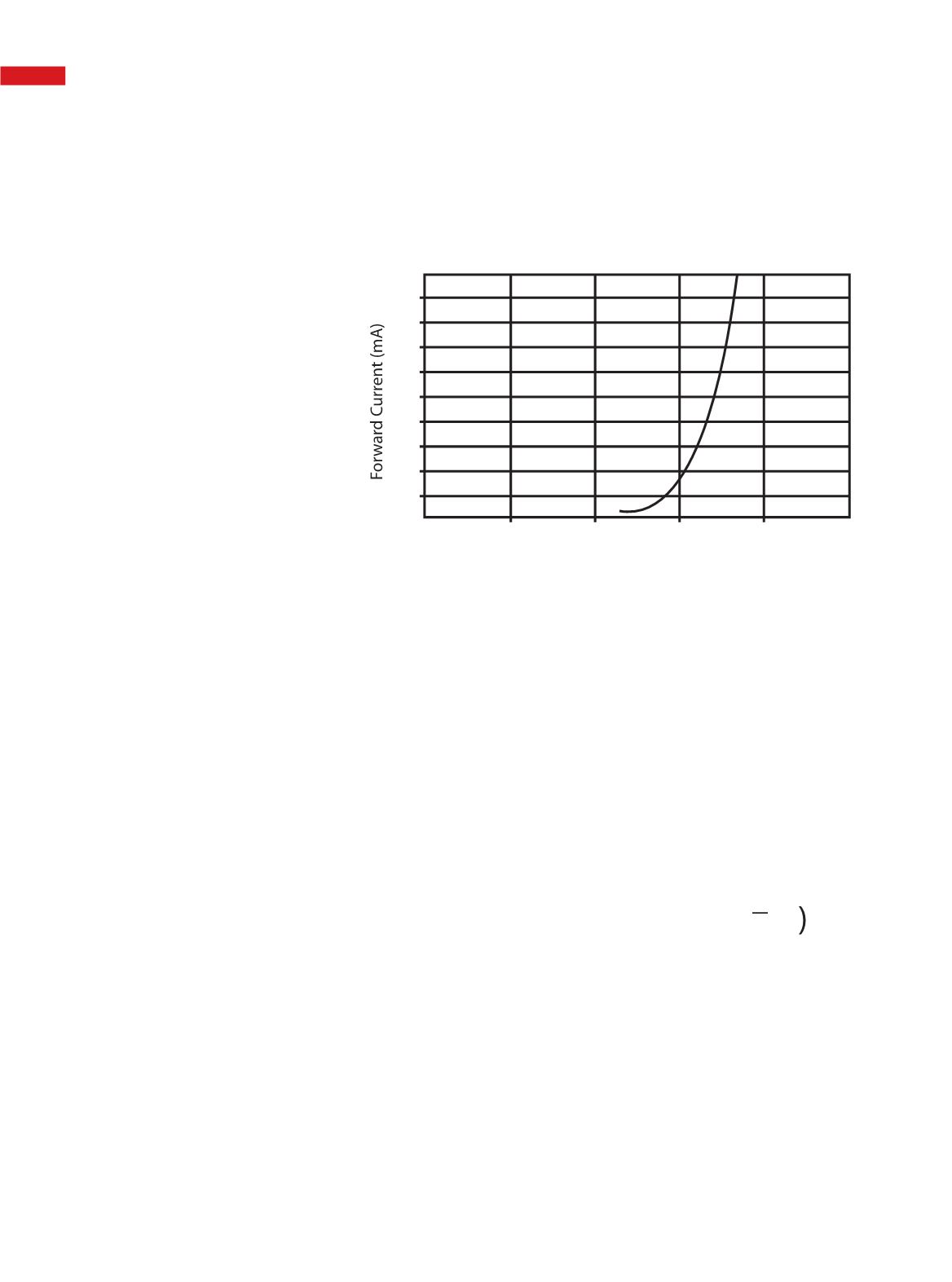

In Figure 1 the forward voltage

characteristic of an LED is shown. The

equation governing the current/voltage

relationship is standard for any semi-

conductor diode:

In this relationship, q is the charge

in coulombs of the electron, V is the

forward voltage on the P-N junction, k

is a constant (Boltzmann constant), and

T the junction temperature (in Kelvins,

i.e. absolute temperature). I

o

is the

saturation (dark) current also flowing at

reverse bias voltage.

Light output as a function of junction

temperature is shown in Figure 2, and

light output as a function of forward

THERE IS MUCH TO BE GAINED

FROM USING DC RATHER THAN

AC AS PRIMARY INPUT FOR LEDS.

PHILKREVELD

EXPLAINS THE

TECHNICALITIES.

0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000

Forward Voltage (V)

I

1-

=

(

I

f

o

aV

kT

e

Figure 1: Forward voltage characteristic of an LED.

GUIDING LIGHT