www. e l e c t r i c a l c o n n e c t i o n . c om . a u

65

a video camera. Shooting videos on

holiday made me realise I had a creative

side, which added to my interest in the

film industry. A great thing about the

job is being surrounded by wonderfully

creative people who are producing

something new.”

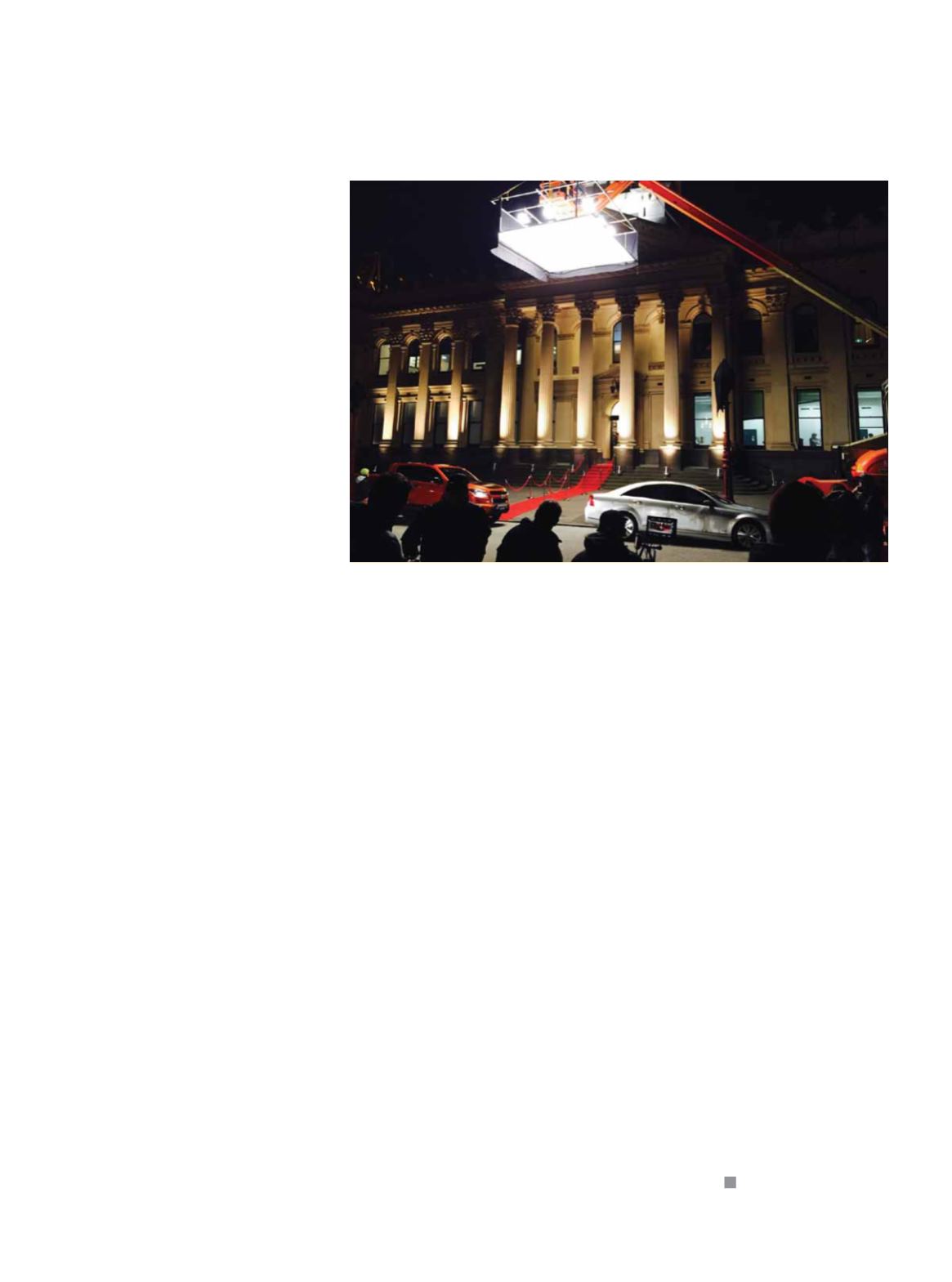

The DOP generally designs the lighting

plan, but they often look to the gaffer

for advice on what would work best.

Jobs in the film industry are highly

sought after, and the role of gaffer is

no exception. Most gaffers work

freelance and have to ‘do their time’ to

become established.

“When big US productions come to

town, it’s a great time to get in because

they employ a large number of people,”

Con says.

“You generally have to start as an

assistant on set then work your way up,

teaming with as many gaffers as you can

to learn the craft and become capable

and efficient. Then you will be ready

when an opportunity comes along.

“When I started at Crawford

Productions I was a transport driver,

then I became a runner, then an

assistant to a grip and eventually

a gaffer.”

Thom Holt of 3 Point Lighting also

became a gaffer in the 1980s, although

he worked in HVAC for eight years

before moving into the film industry.

“In 1985, a mate who works in film

lighting had just started his own lighting

truck business and invited me to have a

look at what he was doing.

“Early in 1986 I went with him to some

TV commercial jobs – no pay, just to

learn the ropes. Five months later a big

car commercial needed lighting staff and

that was my first paid gig.”

Thom didn’t set out to be a gaffer

and admits to being a bit jaded while

changing over to the role. But once on

his feet he never looked back and found

his previous experience in HVAC to be a

big help.

“Being able to work with, understand

and manage electrical equipment,

systems and power infrastructure is

highly valuable. Lighting is not just

about pointing lights around; it’s about

the power supply and infrastructure

that supports a film set.

“You also need to have some

understanding of cinematography,

cameras, lenses and how light reacts

in different situations. You must know

how to use light – manipulate and

control it – and how that relates to

the camera.”

Thom says a typical day as a gaffer

involves a meeting with the DOP to

put a basic lighting and power plan

into place, while the lighting team is

unloading equipment and setting it up.

“When the actors are rehearsing

in the space, the team fine-tunes the

lighting. You should get information

from the DOP for the next shots and

angles so you can start to prepare for

the next moves. The challenge is to get

ahead but remain flexible, because it’s

a creative environment and things are

always changing.”

Due to the constant changing,

efficiency and safety are crucial.

“When changing locations five times

a day, the time pressure is on and

logistical management is paramount,”

Thom says.

“Then there’s team management –

knowing your team’s skills and getting

the job done on time. Then when the

director calls ‘wrap’, you pack it all up

and put it all back in the truck.”

Thom says the volatile industry

requires a big financial commitment.

“If you like reliability and security,

it’s probably not the game for you. On

the other hand, you end up in a lot of

different places, working with a lot of

weird and wonderful people. That is

hugely rewarding and enriching, more

so than most jobs I’ve seen.

“I’ve had a lot of fun moments along

the way. I worked with Buzz Aldrin and

I’ve worked on

Lord of the Rings

and on

Robinson Crusoe

in New Guinea.

“I’ve had the privilege of working

with many great people, and that’s the

best reward.”

The gaffer, or ‘chief lighting technician’, is responsible for taking a lighting plan, as

envisioned by the director of photography, and bringing it to life.