Trade careers and stigma

The Vocational Education and Training sector should urgently fight back against the push for a university education. James Tinslay puts the case forward.

The Vocational Education and Training sector should urgently fight back against the push for a university education. James Tinslay puts the case forward.

If it wasn’t so tragic for the community, especially young people, it would be laughable.

Consider a school careers night at which parents and children are being addressed by various experts about future work opportunities.

ADVERTISEMENT

These sessions can last a couple of hours, and it’s not unusual for trade or vocational education to be absent from the discussion.

Vocational education and training (VET) is stigmatised as second class in post-school education – and that view comes from the Business Council of Australia reporting on problems in the VET sector.

There’s a suspicion that taking up a trade means a low-income career when universities are offering exciting and sexy sounding courses liberally sprinkled with terms such as artificial intelligence and quantum mechanics.

As one managing director recently said: “I’m sick and tired of hearing that 80% of the jobs of tomorrow haven’t even been thought of yet.”

That very much resonates with me.

Industry associations such as the National Electrical and Communications Association (NECA), Master Plumbers Australia and Master Builders Australia have done much to train young people for industry via careful selection and employment. They have done so almost entirely through not-for-profit structures.

However, these organisations have limited access to schools, hence to young people in their formative years. Fundamentally, it is government, schools and parents that have access. For anyone else, gaining access to parents and students is difficult and expensive.

The electrical industry has fared relatively well with apprenticeship numbers via the competency of NECA’s group training organisations and other similar not-for-profit organisations.

Yet we are still missing out on young people, who are generally influenced to ignore what they are good at and told they must go to university.

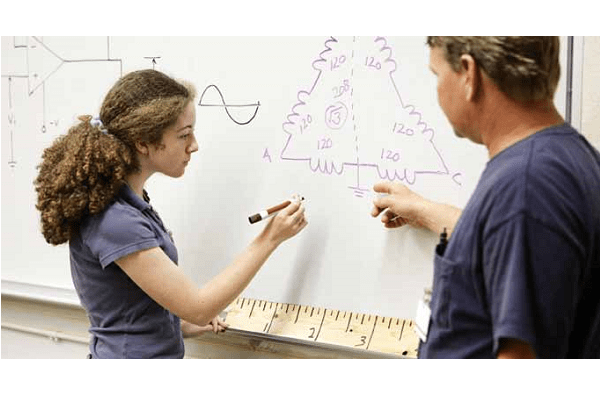

Youngsters can’t comprehend a career as an electrician and the opportunities it opens up for those with the ambition to go into management and potentially become industry leaders.

As with many problems in industry and society, the answer rests with government.

VET funding has been provided by state and territory governments, which covered well over 50% of the costs.

The Federal Government has criticised the states for not meeting their share of the VET burden, yet it has caused some of the worst errors in the sector.

The feds recently introduced the Skilling Australia Fund and allocated $1.5 billion over four years.

NECA has been one of the beneficiaries of the imminent industry specialist mentoring program, which aims to get more people into apprenticeships. I have no doubt that the mentors employed by NECA and similar organisations will do a great job guiding young people into our industry.

However, it will be a relatively short-term boost. The money will run out and Canberra will think that it has done a wonderful job, despite the lack of sustainability in such programs. I don’t know the answer, but anybody with an interest in the electrotechnology sector should make this a discussion point with young people considering what to do in life – and their parents.

There is a remarkable story to tell about VET and everyone can add their voice to the campaign for change.

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT