Future sight: What’s the solar industry going to look like?

The way we consume electricity is changing and sparkies are at the forefront of the revolution. Clairvoyant Phil Kreveld looks at what life will be like on the tools in the near future.

The Australian Labor Party (ALP) commissioned report, Castles & Cards: Savings in the suburbs through electrifying everything, predicts that electrical energy use will be tripled as the typical home looks to electrify everything. It’s projecting a rise in electrical energy consumption from the present average of 13kWh/day to 37kWh/day.

ADVERTISEMENT

Castles and Cars is a part of ‘Rewiring The Nation’, an ALP policy initiative it took to the polling booths last election. It waxes enthusiastically about the CO2 reduction available if we generate electricity from renewable sources.

AEMO’s 2022 Integrated Systems Plan (ISP) indicates that by 2050, distributed generation, i.e., connected in distribution networks, is forecast to be 70GW. The expectation is that we will all be driving electric vehicles (EVs) and that would help in bumping up solar system installations. The potential for domestically generated electricity can be based on the current eight million private dwellings, each with a roof area of 240m² as a guesstimate. Assume about a third of the roof area is suitable for solar panels providing 640 million square metres at about 0.3kW per square metre or in aggregate power terms 192GW representing well over ten times of present aggregate demand.

Australia already outranks the rest of the world in renewable energy generation per capita and it doesn’t look like we will get bumped off the winner’s place on the podium. The potential power that could be generated by distributed generation is so large that there are questions like ‘why are we building Snowy 2.0?’ Well, let’s keep that project going but ask what solar and distribution might look like by 2030 when we arrive at the target of 83% of electrical energy being generated by renewables.

That brings on the flood of renewable certificates generated by the growth in solar systems. Small-scale technology certificates (STCs) are currently trading at something of the order of $37 but what will happen after the deeming period, scheduled to end in 2030? If electricity energy prices go down as the Commonwealth Government keeps promising, there might well be a slowing demand for solar – and a surplus of uncleared certificates.

Distribution networks could be energy independent

The increasing purchases of rooftop solar are due to high electricity prices and they’re unlikely drop at present. The steady increase of distributed solar system concentration is affecting distribution networks but with few exceptions, network providers do not seem too keen to invest in what we might loosely term as upgrades.

A consequence of solar expansion may well require new maintenance policies regarding their efficiency and longevity, no different to what is required for the smoke and steam-belching coal-fired power stations.

As Audrey Zibelman, the erstwhile chief executive of AEMO put it in an ABC 7:30 Report interview in 2020: “We don’t know what the mums and dads are planning around the kitchen table” – and we still don’t know. More recently, at an AEMO stakeholder’s webinar, a question was raised as to why transmission network planning doesn’t seem to consider the growing energy independence of distribution networks. The answer was: “We did think a bit about it but not for our planning”.

Rather than ridiculing AEMO – it has a lot of technology talent in its ranks – take it as an indication of the state flux and uncertainty bedevilling Australia’s electricity system.

Presently, over three million installations account for 15GW capacity or 5kW capacity per installation. Over half of those homes would have solar by 2032, rising to 65% with 70GW capacity by 2050, according to AEMO’s latest ISP.

Total capacity by 2050 in the National Electricity Market is forecast at 280GW and about a quarter of that energy demand is forecast to be met by rooftop solar. The numbers do suggest the possibility of distribution network independence or partial independence.

According to predicted population expansion, there will be 15 million domestic dwellings by 2050. The solar generation capacity figures don’t quite jell in terms of projected solar capacity but then, the domestic dwelling numbers might have been projected on the low side. The Castles & Cars projection is for an average electrified home consumption of 37kWh per day or an average demand of 1.5kW but that can be expected to peak two or three times in the early evening and have a steady component for charging the family EV (or two).

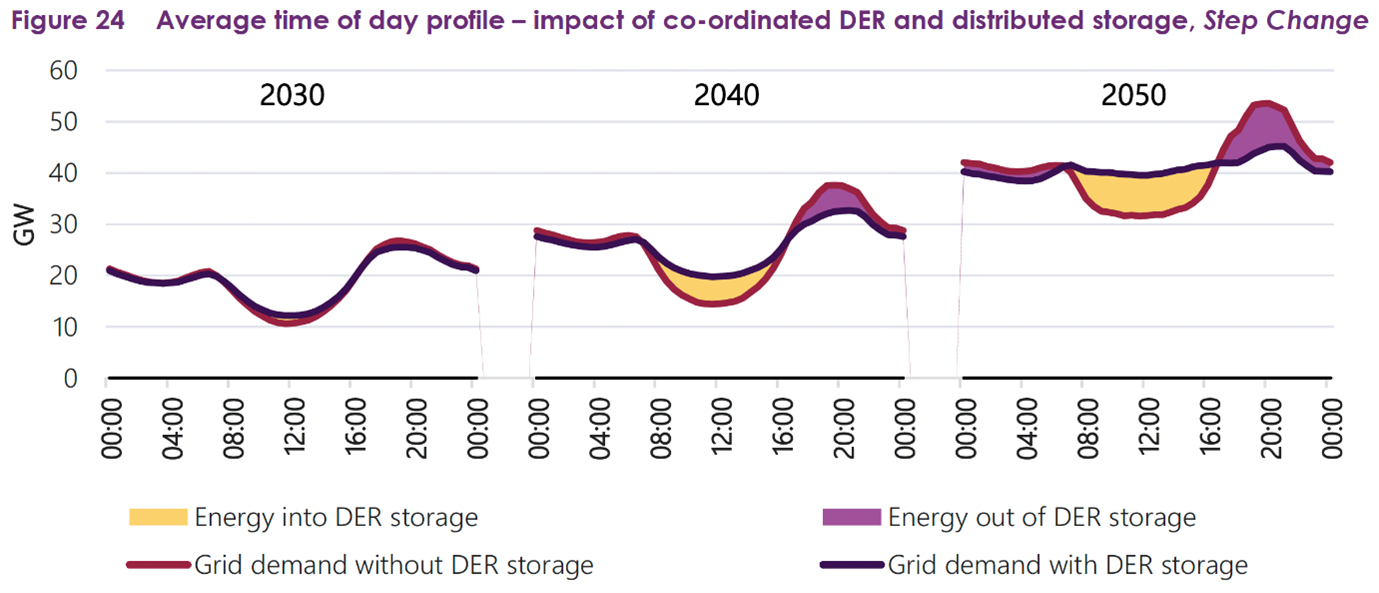

In energy terms, that amounts to an eyewatering 240TWh, in other words, a smidgin less than Australia’s current annual consumption of electricity. Figure 1 is of AEMO’s ISP, indicating that distribution customers would be close to energy-independent by 2050 and as shown based on rough calculations, there ought to be plenty of scope to expand domestic electricity production.

Technically, by 2050 just about all generation will be based on inverters with the exception of Snowy 2.0 and maybe some hydrogen gas turbine-powered synchronous generators. Tasmania, the battery of the nation, will be connected to the mainland by Basslink and Marinus but these are DC links, i.e requiring inverters for connection to the mainland grid.

Right now, nobody knows if all that inverter hardware will provide a stable electricity grid because it hasn’t been demonstrated anywhere else in the world on the scale being contemplated in Australia. Something not getting publicity is the minimum power flow in transmission lines. The more power being generated in distribution networks the less needs to be transmitted by external generators making voltage control on transmission lines problematic. Transgrid is purchasing controllable shunt reactors for this purpose – they will be used for the VNI West interconnector between NSW and Victoria.

In general, large fluctuations in transmitted power will pose voltage stability problems that we have yet to solve. Daniel Westerman, chief executive of AEMO described this as “riding a bicycle very slowly” (and staying upright). In a talk he gave at Melbourne University last year, he mentioned that AEMO saw the necessity for something of the order of 40 synchronous condensers to keep the grid stable, voltage and frequency-wise.

There is a cool 1.5 billion dollars someone must find and it is considered necessary because of the retirement of old-fashioned synchronous generating plants.

Investment in distribution networks

Distribution networks are having their own problems, i.e., voltage control aided and abetted by reverse power flow because of rooftop solar. That is a reason for limiting power export from solar. One way of absorbing excess power is via community batteries and these also provide (at least in theory) for the creation of microgrids within distribution networks. Distribution network service provider, Jemena, is trialling a small carveout comprising of a battery and voltage-forming inverter.

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT