Waste not, want not: reusing solar panels

The growth in photovoltaic (PV) installations could swamp us with unwanted modules in the future. GSES issues a rallying call for national action.

Most photovoltaic (PV) modules have a life expectancy of 20-30 years unless they become damaged, defective or less efficient.

The number of decommissioned PV modules is expected to increase rapidly in the coming years as early adopters replace their systems.

ADVERTISEMENT

The challenge of dealing with redundant components such as PV modules is yet to be solved in Australia and it will become a critical issue.

Without proper policies and procedures, most will end up in landfill. This poses a threat, as some technologies contain toxic substances that could leach into the environment. This article is intended to stimulate interest, as opposed to detailing the status of recycling in Australia.

Benefits

Recycling PV modules offers the benefits of reducing landfill, creating green jobs and producing revenue from recovered raw materials.

This recovery and reuse is known as the ‘circular economy’.

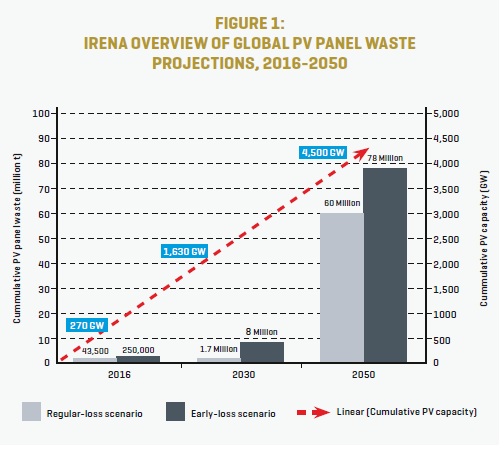

A 2016 report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates that global waste from PV modules will be about 78 million tonnes by 2050 (Figure 1).

However, the report also says there is enormous value to be gained from PV module recycling – about $US15 billion

($A21.75 billion) globally.

There is also vast potential in recycling other system components such as inverters, batteries, production waste, etc. Categories such as lead acid battery recycling constitute mature industries, and e-waste recycling is growing.

The IRENA report investigated two scenarios to forecast PV module waste:

- regular loss – assumes a 30-year lifespan for solar panels, with no early attrition; and,

- early loss – takes account of ‘infant’, ‘mid-life’ and ‘wear-out’ failures.

Assuming a best-case scenario of regular loss, there will still be 60 million tonnes of waste globally by 2050. In comparison, Australia generates about 67 million tonnes of every kind of waste each year.

Components

Although many PV module technologies are available, the structure and components of the most common (crystalline) modules are fairly consistent.

Modules are constructed from several components bonded together, and about 90% of these materials (by weight) can be recovered and used in other industrial sectors:

- aluminium

- glass

- solar cells

- plastics; and,

- silver, lead, copper and cadmium depending on the solar cell technology.

Modules not based on silicon have an even greater recovery rate of up to 98%. So why are we not recycling all our PV modules when so much material can be recovered?

Recycling modules is a complex and expensive process, and relatively immature industry in terms of commercialisation.

Some components, such as the glass and aluminium frame, are relatively easy to reclaim. However, separating the encapsulant, solar cells and metals incurs higher costs. Then there’s the cost of uninstalling modules and transporting them to a recycling plant.

PV recycling technologies are still in the early stages. As is the case with all industrial technologies, the costs involved will decrease as the process becomes simpler and more efficient, and value chains are established for the materials.

Disposal

Due to the increasing number of unwanted PV modules, some countries have established recycling processes.

One company providing PV information to suppliers and customers, ENF Solar, has a list of 54 recycling businesses worldwide.

The countries with the highest number are the United States and China, each with 12. However, the European Union has a larger number in total.

The relative success of the EU has stemmed from PV-specific legislation under the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive.

Since 2014, all manufacturers supplying to any European country have been responsible for the disposal and recycling of modules – and for financing all costs.

The Australian company Reclaim PV Recycling was founded in 2014. It launched the nation’s first commercial PV module recycling plant in mid-2019 and collects up to 1,000 units a week.

At this stage the Adelaide-based business deals only with Tier 1 manufacturers and Clean Energy Council (CEC) accredited electricians. However, it plans to expand as operations become more efficient and cost effective. It also recycles PV components such as inverters, array frames, packaging and more.

Other companies list PV product recycling, but the extent of these activities has not been investigated by GSES.

As an example of state-based initiatives, from 1 July 2019 Victoria has banned the disposal of electronic waste, including televisions, computers and all PV system components, as they are “designed for the generation of an electric current”.

To support this change, the Victorian Government is investing $16.5 million to upgrade collection and storage facilities. It estimates that Category F (leisure and PV items) will have increased from 14,575 tonnes in 2015 to 46,785 tonnes in 2035 – most of the growth being PV module waste.

Some companies, such as First Solar (non-crystalline technology), have tackled their corporate responsibility obligations by implementing recycling services. This is a great start, but there is much more to be done.

There are 3,140 models of PV module from 77 manufacturers on the CEC approved list. Australia needs to develop policy frameworks, education campaigns, funding and resources to promote strong and ongoing research and development.

Initially, funding could be a barrier until efficient technologies and value chains are established. Stakeholders must pool resources and knowledge to boost recycling before the nation has a huge PV waste problem.

A logical path would be to build on the federal government’s National Television and Computer Recycling Scheme, which was established in 2011 to provide householders and small businesses with access to industry-funded collection services.

Australia has the Product Stewardship Act, which mandates how e-waste is dealt with, and the plan is to include PV modules.

There is also an overarching policy that was updated in 2018 to embrace ‘circular economy’ principles. For more information, please visit the National Waste Policy site.

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT