PHIL KREVELD: Right on the roof

Panel installers must study location and roof type before quoting, writes Phil Kreveld. Mounting materials are costly, labour time may increase, and an unhappy customer is bad for business.

Panel installers must study location and roof type before quoting, writes Phil Kreveld. Mounting materials are costly, labour time may increase, and an unhappy customer is bad for business.

One of the major risks when you install a photovoltaic system – besides falling off the roof – is an installation malfunction.

Your reputation as an installer is also in jeopardy.

ADVERTISEMENT

Immediate thoughts go to the electrical side of such a project, but the longevity of an installation also relies on the mechanical workmanship in putting the system together.

A rooftop photovoltaic (PV) system is subject to weather that can severely restrict its useful life. Installation costs are considerable in a typical domestic system, and competition means there’s a temptation to cut corners in areas that don’t relate directly to electrical performance.

However, compromising the structural integrity of a rooftop installation is a bad idea – even a dangerous one.

PV panels are not something to just ‘stick’ on the roof. They are part of the structure, and the expertise usually associated with construction comes into play.

In addition to the mounting system there are other crucial aspects:

- Resistance to weathering (particularly corrosion).

- Secure fixing to the roof structure.

- The condition of rafters and lintels in older homes, especially in relation to wind, which sets up conical vortices at the edges and corners of roofs. Under wind velocity of more than 60m/s, vortices can exert great forces on panels.

So installers should at least be aware of the Australian Standards applying to rooftop installations. They should also carefully scour the technical literature from reputable suppliers of rooftop installation equipment.

Working at height among potentials of hundreds of volts is dangerous. A single panel typically has open circuit voltage of 30V DC or more, and the string voltage of 12 panels will be about 400V.

To avoid any chance of electric shock when panels are being installed, no electrical connections should be made. Once the panels are in place, and before wiring is commenced, it’s a good additional precaution to cover them with blankets, etc, until wiring is complete.

Malfunctioning of the PV panels at installation time is unlikely other than through obvious damage sustained in transport. However, performance degradation takes place over time. It’s a matter of degree, but bear in mind that the householder pays for this.

Rooftop panels should be facing as close to due north as possible. Otherwise, they should face north-east. If sufficient power is not available on one side of the roof, another set of panels (eg: west facing) can be installed.

The inverter for this arrangement requires two maximum power point trackers (MPPTs). Panels that are unequally illuminated should not be paralleled other than via two MPPTs. If connected in series their efficiency will be badly affected.

Orientation can be a problem. A 30-degree roof slope is generally adequate, but roof mounting hardware to elevate the angle of the panels is available.

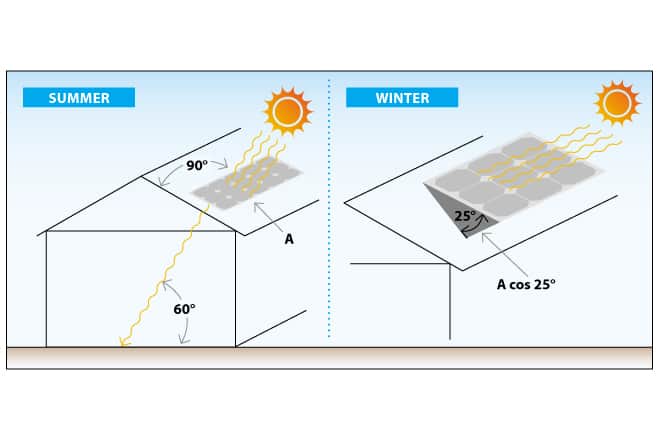

Without going into theory, the orientation is best explained with a panel facing due north (Figure 1). A 30-degree roof facing the midday sun at an elevation of 60 degrees gets the sun’s rays at 90 degrees to its surface. This is ideal.

In winter, the sun might be at 35 degrees elevation. The effective illumination of the panel is equal to the cosine function of 25 degrees (check the diagram for the definition of angles) or 90.6% of the maximum value.

If the roof is flat the illumination will be 57%, which is well down. A minimum tilt of 10 degrees allows for self-cleaning.

If the panels are tilted on the roof, ensure that they don’t cast shadows on each other (the standard tilt angles available are 5 and 15 degrees).

Slate, tile and steel roofs require different mounting methods. In all cases the panel-securing hardware will be attached to battens or purlins, but the leak-proofing methods will vary.

Fixing to purlins is generally preferred, but the installer needs to check the location carefully before the installation date. Steel roofs require fixing of panel hardware by means of rubber pads, which provide leak proofing and isolation.

The isolation aspect is important, as nearly all solar systems have only a safety ground. The functional ground is absent in a transformer-less inverter installation, but earth leakage current flows via the capacitance panels have to ground nevertheless. For a steel roof this can be considerable.

Apart from the power considerations that determine the number of panels, wind conditions have to be taken into account. As a rule of thumb, mounting panels close to the edges of roofs should be avoided.

The Northern Territory, northern Queensland and Western Australia are subject to cyclonic conditions, so installations must adhere to Australian Standard (AS) 1170.2.

Although panels look like part of the roof, they are separated from the roof surface by an appreciable distance. Wind exposure causes lift and drag forces on the panels that increase as the square of wind velocity. The higher the roof pitch and panel location the more pronounced the effects. Sufficient anchoring to the roof structure is crucial.

In planning roof fixtures, first look at the location. (For simplicity’s sake a conventional pitched roof is assumed.)

If the installation is in Brisbane (region B of the Australian Standard) the anchoring points for the solar panel fixtures will increase. Brisbane is subject to higher wind speeds than Melbourne and most of the south coast (region A).

Next, the roof is divided into three equal zones: a central zone and two end zones. The end zones bordering the roof edge are subject to higher wind speeds than the centre, so the anchoring points and number of rails will increase.

There must also be an exclusion zone so that panels are not mounted right on the roof edges.

The terrain categories must now be considered. Open country without windbreaks is the worst situation, compared with built-up areas.

A combination of open or built-up terrain and wind speed region determines the number of anchoring points per rail. Installers should consult their supplier for appropriate engineering detail.

The ‘install and forget’ mentality that marks much of the industry is not helpful, because installations degrade over time.

The quality of roof-mounting materials has quite a bearing on the effective lifespan of the installation. The weather can promote galvanic corrosion; dissimilar metals and water being the ingredients. Oxidation can halt corrosion – but don’t count on it.

Marine and industrial environments can speed up corrosion. Sulphur dioxide and nitrous oxides in industrial and heavy traffic areas, and chlorides in seaside locations, require precautions to be taken.

When in doubt, seek ways of physically and electrically separating potentially problematic metal combinations. Using rubber washers to isolate galvanised screws from painted steel sheet is common practice in the roofing industry. Stainless steel washers with an ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM) gasket adhered are commonly available from hardware suppliers.

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT