One small step for Parkes telescope electrician

It was one giant leap for mankind, but for Parkes telescope electrician Ben Lam, 20 July 1969 was just another day on the job. Anna Hayes spoke to the retired electrician about his memories of a historic moment.

Fifty years have passed since the iconic moment when Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon, but the legacy of that time is something that has lived long in the public consciousness, particularly at the Parkes radio telescope site in New South Wales.

The telescope was instrumental in broadcasting all but the first nine minutes of the moon landing transmission in 1969.

ADVERTISEMENT

Present on the day was site electrician and telescope driver Ben Lam, who says that it was all in a day’s work.

“The council decided to have a big celebration for the 40th anniversary of the telescope. Before that we never really talked about [the Moon Landing] – it was just something that happened and we carried on normally, never making a big thing of it,” he says.

The celebration and acknowledgement of the NSW location’s part in history is getting bigger all the time, Ben says, and, with that, so too is the interest in all things space-related.

“We had an open day at the telescope recently and they had over 6,000 people there. We used to have open days during the year – they always got quite a few people but this time I think there was over 20,000 people over the two days. I’d never seen anything like it!”

The Royal Australian Mint has launched a series of limited edition dome-shaped coins as part of a commemorative set with the United States Mint.

Originally from the Netherlands, Ben was a first-year electrical apprentice when he moved to Australia. He arrived on a Saturday and began work as apprentice two days later in Warren, NSW. He was working as an electrician in Dubbo, NSW when the job at Parkes came up.

“I was looking for a job that was secure. I put in for this one and I got it. I was there for over 30 years. I remember asking the boss about job security and he said he could guarantee me 10 years. That was 60 years ago and the telescope is still going, strong as ever.”

Ben wasn’t just an electrician on site but he was also rostered to drive the telescope, which involved night shifts.

“For the first 15 years I used to work about 18 or 19 hours a day. Your normal day was 8am to 5pm and if you were

rostered, you’d stay back and drive the telescope until 1am. Then you’d go home and be back again at 8am to do

the same thing again.”

The telescope was in operation 24/7 with about eight drivers on the roster for driving duty.

Outside of driving duties there were various electrical tasks mostly relating to the upgrading of equipment at the site. About 15 years after Ben joined the staff at Parkes, a huge upgrade of the telescope motors was carried out in order to computerise the movement of the scope.

The preparation at Parkes happened well before Neil Armstrong even got near the moon, with NASA installing an array of equipment to assist in the broadcast. The site also tracked the Apollo 11 module for about a week prior to the actual landing.

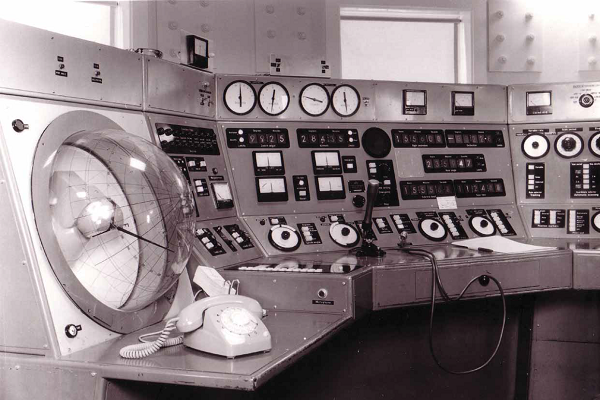

“Whoever was driving the telescope had to find the module, log onto it and stay with it all the time. It was very dicey because when the module got behind the moon you lost the signal so we had to wait until it got to the other side to

pick it up again – that was the hardest part. It wasn’t just sitting there using the controls, it was watching the dials all

the time so it wouldn’t get out of sequence – you had to make sure you were right on it, otherwise you lost your signal and had to try to find it again.”

As Parkes’ big moment came around, the unpredictable Australian winter weather reared its head, walloping the

NSW site with high winds and even hail stones, and providing the sternest of hallenges for the crew manning the

machinery inside.

“With the telescope, if the wind blows more than 30mph you can’t tip it down to 60 degrees. Now just an hour before

the module came up, the wind got up something terrible. I said to the boss John Bolton, who was the director at Parkes, that we should switch to our own diesel rather than the council power supply because if we got a blackout we’d lose everything. We couldn’t afford that so we switched over to our diesel. So right through the moon shot I was pretty busy making sure the diesel didn’t fail. We kept it going all the time.”

It was all in the timing – the moon rose into the Parkes’ telescope’s field of view just as Buzz Aldrin switched on the module TV camera, and Parkes began tracking the events. Less than nine minuteslater, the moon had risen into a better position and Houston switched to Parkes’ feed for the remainder of the two-and-a-half hour moonwalk.

Ben says that while it was an exciting time it wasn’t something that hit any of the staff at Parkes’ other than knowing that they had been involved in.

He recalled watching the action on a small screen on site.

“It was pretty blurry but you could see him stepping on the moon and we thought it was nice, you looked outside and you could see the moon right there and you wouldn’t think that there was a fellow walking on it so far away!”

Ben says that it is only in the last few years that there has been increased interest in the local involvement in the moon landing. In 1969 however, for the team at Parkes’ everything carried on as before.

“We just kept going, kept working. Things at the telescope changed all the time; even when the Apollo program finished there was always something new coming up.”

Working at the telescope didn’t come without the odd colourful anecdote.

“When you were on the night shift, quite often we’d get phone calls and the person is saying that if we look south we’d see some funny things. You’d have a look and it’d be a farmer on his tractor! People thought there were seeing UFOs or something – we’d get that call quite often but we never saw anything!”

After more than 30 years at Parkes, Ben retired. He and his wife Toni have three sons. Ben and Toni still live in Parkes, the telescope where he spent the majority of his working life in close proximity.

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT