Breaking free: Inside a modern standalone solar build

We could do with a more holistic appraisal and development of Australia’s renewable transition, not only for rural communities, but even urban, off-grid installations. Phil Kreveld explores one successful project and how it works.

Australia has the highest rooftop solar capacity per capita in the world. It’s an underexploited resource to such an extent that there is cause for contemplating off-grid operation!

ADVERTISEMENT

This might appear to be a controversial statement, but the fact is that if, instead of grid-following (i.e. phase-locked loop (PPL) controlled) inverters, only hybrid inverters were being used, some three-million-plus solar installations would be a step closer to independent operation.

But that doesn’t result in much money for the power distribution companies, the ones who have had a healthy hand in consumers’ pockets for as long as we could flick the lights on.

Despite this, there are installations out there with people living completely independently of the power grid. I was able to visit one while conducting research for this article, a perfectly-timed article (if I do say so myself), as the off-grid draft standard, AS/NZS 4509.1:2025, is open for comment as of October 2025.

For more detailed information on the draft off-grid standard, you can find it on Standards Australia’s website. But for my take on what goes into a true independent installation, continue reading (Please note, several diagrams referenced in this article are created by me for this article, not part of the draft standard. Table 1 comes from AEMO.)

Rooftop energy in danger of swamping large-scale generation

There are 3.4 million residential rooftop solar installations and 130,000 commercial rooftop installations under 100kW, nationally. The average size for residential systems is 8kW, and for commercial systems, 28kW.

The aggregate residential capacity is 22GW, but because of network hosting limits, it is closer to 15GW, and for commercial installations, less affected by export limits, it is probably close to the aggregate capacity.

In total, small-scale solar’s actual generation capacity is around 25GW. The annual national electricity consumption is 230TWh, or an annual average demand of 26GW.

The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) forecasts a doubling of annual electrical energy by 2050, with an aggregate generation capacity of 300GW, of which 100GW is self-generation. This includes growth in small-scale PV and also rooftop installations. Allowing six hours of high-intensity daylight, approximately 200TWh, would be self-generated energy. The remaining 200GW capacity would service another 200TWh, ~20GW capacity and a capacity utilisation of one in ten compared to one in four for self-generated energy.

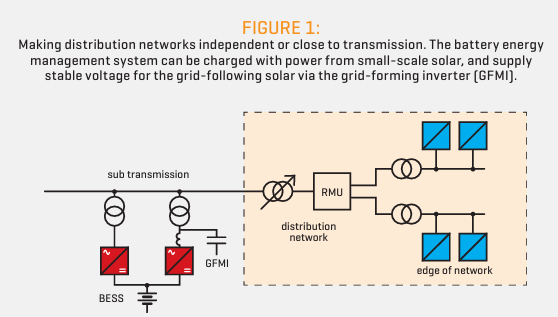

AEMO is counting on virtual power plant (VPP) participation in the energy mix. VPP schemes appear sensible up to a certain aggregate limit per substation in that negative power flow into sub-transmission is not always permitted. Transformer power limitations and on-load tap changer, low-tap re-engineering (to allow for higher voltage caused by reverse power flow) require lots of capital expenditure in distribution networks. VPP aggregators make their money by reducing energy demand from transmission networks, which are capacity-limited, as are the large-scale variable renewable energy (VRE), coal and gas-fired generators.

SunWiz managing director and advisor for solar, Warwick Johnson, is quoted on the lack of trust and information about VPPs. Given the uncertainty of financial benefits, the uptake amongst those eligible for the NSW battery rebate of $1,500 for 27kWh storage (provided the battery is part of a VPP) is faltering. Victoria provides up to 80% interest-free loans, and the Commonwealth, up to $1,400. This is now replaced by the Commonwealth Cheaper Home Battery program, a rebate scheme based on small-scale technology certificates (STC), and therefore resulting in a discount provided by the battery supplier.

Apart from VPP, other moves are afoot to utilise rooftop generation potential. Ausgrid’s application to the Australian Energy Regulator to install 130MWh battery capacity in its Mascot-Botany and Charmhaven (north coast of NSW) distribution networks has set off vigorous protests by AGL with accusations of anti-competitive behaviour. Ausgrid’s reasoning is that the proposed battery capacity will allow it to soak up excess household and business rooftop generation in daylight hours, and to provide the energy back to consumers in the hours of darkness. If the rulebook is forgotten for a moment, distribution networks could be close to self-sustaining and take the pressure off transmission line construction and more renewable energy zones.

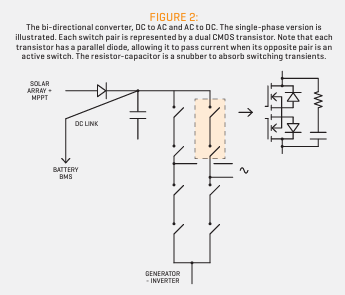

Table 1 shows that distribution networks rate voltage and phase balance problems due to solar feed-in as the main ones. From 2022 onwards, starting with South Australian Power Networks, distribution networks began the task of restricting export power output from solar inverters, utilising the Common Smart Inverter Profile (CSIP) based on the IEEE 2030.5 communication standard (AS 5385:2023). The CSIP addresses the difficulty of voltage control in medium and low-voltage networks.

Emergency Backstop (applying to inverters supplied post October 2024) is just the latest wrinkle and will be invoked by AEMO when it has voltage control problems on high voltage transmission lines caused by very low power flow.

More than 90-plus percent of electrical energy is absorbed in distribution networks. Therefore, if rooftop solar is capable of meeting energy demand, or is getting closer and closer to that level, why all the renewable energy zones and big transmission projects?

If it weren’t for the phase-locked loop (PLL) as an integral part of nearly all small-scale (grid-following) inverters, there would be much less need for distribution networks. The foregoing is a good introduction for off-grid generation.

Off-grid and a review of inverter/battery engineering

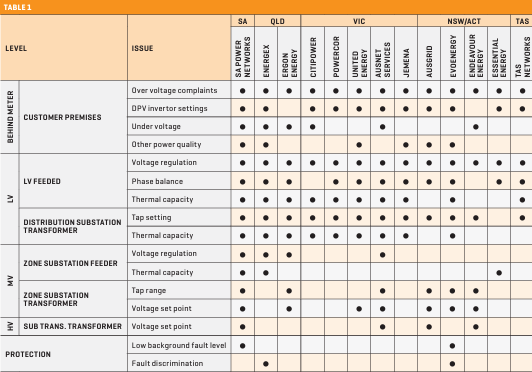

An inverter is a bridge circuit of either two arms (single phase) or three arms (three-phase), with either two switches per arm (unidirectional power flow) or four switches per arm (bidirectional power flow, see Figure 2).

Power flow can be DC, i.e., to charge batteries, or AC for AC loads or power export to the grid. Alternating current is generated by a sine wave, pulse-width modulation. Direct current is generated by controlling the firing of the switches at a controllable phase angle of the AC voltage input.

By means of control circuitry, an inverter can be a grid follower, requiring a PLL to ensure that the current is in phase with the grid voltage or at some fixed phase difference to the voltage. It can also be a voltage-forming inverter for hybrid or off-grid operation. Inverters can also have both modes of operation.

Either way, current (grid following) or voltage (voltage forming) is limited by the DC voltage on the DC link capacitor. The solar panel maximum power point tracker, or battery pulse width voltage controller, requires a voltage boost circuit for off-grid voltage forming.

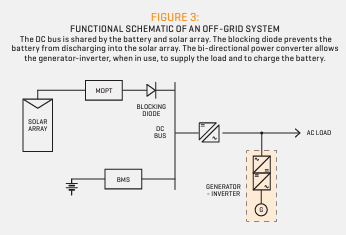

As for many hybrid architectures, the use of batteries necessitates either a maximum power point tracker-charge controller or a plain vanilla charge controller. The MPPT-charge controller may be the better option, utilising the maximum power available from the solar panels. Typically, the DC input voltage requirements will be lower than panel voltage for either type of charge controller, thus limiting the panel string count, typically of the order of 90V.

A charge controller without MPPT may well be satisfactory, given that charging voltage and current will usually be supervised by a separate battery management system. The inverter for a battery installation will require a DC link voltage higher than the output AC peak voltage, thus having to include a non-inverting DC boost circuit, as battery voltage is anywhere from 30V to 50V.

Although there is flexibility in layouts, the scheme as shown in Figure 3 is typical. The DC bus is a low-voltage one, in accordance with battery voltage. The inverter supplying the load is bi-directional.

LiFePO4 batteries have a low self-discharge rate of under 3% per month and are considered a lower fire-risk than Lithium batteries. They are best stored at a 50-60% state of charge (SoC) to prevent degradation and can last for thousands of charge-discharge cycles, which are heavily dependent on the depth of discharge (DoD) and temperature. Higher temperatures significantly degrade cycle life, with increased discharge rates also reducing the number of cycles.

Voltage forming

Voltage-forming inverters are, in essence, the same animal as grid-following ones. The former has to contend with loads with varying power factors.

Residential loads have power factors, anywhere from 0.8 (bad) to 0.9-plus (lagging). These days, leading power factors can occur because of LED lighting, large entertainment equipment and inverter drives for HVAC. Leading power factors are becoming an increasing problem for distribution networks because, in combination with reverse power flow from solar, transformers are subject to magnetisation from the secondary side, leading to over-fluxing and high hysteresis losses, and significant harmonic distortion of voltage.

All off-grid installations require storage batteries and stand-by generators. The generators can be engine-driven slip-ring alternators, capable of running loads via a change-over switch, or be part of a ‘bump-less’ system, without any interruption to supply. The solution is provided by the generator-inverter. In this system, the alternator’s AC voltage is rectified to supply the DC link of the inverter. As shown in the diagrams, the inverter can load share with the battery-inverter.

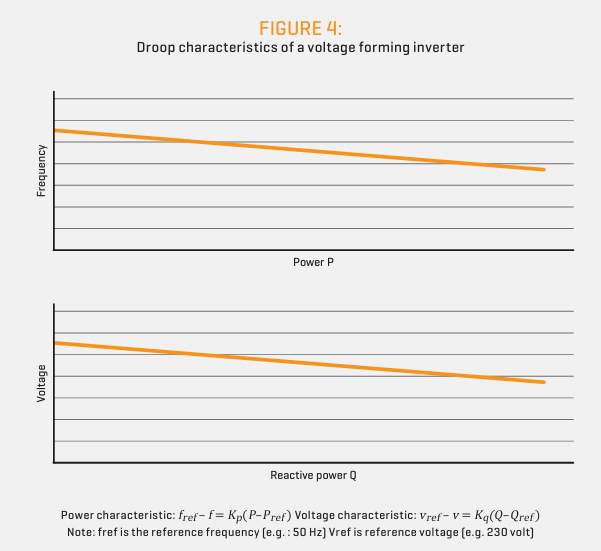

Load sharing requires droop control, whereby frequency and phase are in step with one another. The standard droop characteristic is power-frequency, and reactive power-voltage (Figure 2). Taking 0.9 lagging as an example, on a per unit basis (power equalling 1.0pu), reactive power would be 0.48pu.

For a business such as a fast-food outlet, reactive power can be substantial. There is some interaction between the power and voltage droop characteristics, but we live in an imperfect world, and distribution 230/400V is allowed to fluctuate between +10% and -6%.

Note, however, that for mainly resistive loads, voltage-power droop is effective. Droop operation is something to ascertain from suppliers. Unlike alternators, which require a tie line for synchronisation, inverters can share the load bus and adjust their power (and reactive power). There is a limitation in that the peak voltage is limited by the DC link voltage of an inverter. The maximum permissible discharge rate of a battery limits power-frequency droop, and a low voltage cut-off to prevent over-discharge of batteries should be a standard protective feature. As shown in Figure 2, the use of a bi-directional inverter allows the solar strings to direct surplus power to the battery; however, only to the limit allowed by the battery management system.

However, going “off grid” is the only possible option in the absence of nearby power and a braver step if connection to the distribution network is available, even if there are substantial connection costs involved.

The economics for a grid-connected system, with battery storage and preferential battery charging over power energy export, essentially provide off-grid economics advantages. However, off-grid for owner-builders can be an attractive proposition in that the mindset is one of not being daunted by technical problems and expands the choice of building sites.

In any event, the installation requires the labour of licensed electricians. Typically, a 5kW off-grid system will be of the order of $50,000 compared to a grid-connected cost of $10,000. The 5kW system illustrated above has a hardware cost of $15,000. By purchasing costly items directly, great savings can be made.

An owner-builder, having done research, should be able to draw up a single-line functional diagram from which the wiring for the premises can be worked out and checked to be in accordance with AS/NZS 4509.1. A licensed electrical contractor must carry out the wiring. The mindset of the owner-occupier has to be focused on regular maintenance. Set and forget doesn’t work.

Insurance limitations should be very carefully considered, apart from the usual ones of inundation and fire, although that may attract add-ons to premiums.

Lightning strike protection, depending on location, should also be considered. Economic considerations should not ignore the danger of a direct lightning strike. Intuitively, it appears that the taller a lightning arrestor is, the larger the shadowed area (protected) surrounding it is.

The challenge in designing protection arises from the inexact nature of protection models. The rolling sphere method of planning lightning protection was developed for the protection of substations and is also useful for designing protection for solar installations.

To minimise induction effects, cable lengths must be as short as possible. For example, in the DC side of the solar system, it’s possible to reduce the cable length of the positive and negative terminals by twisting the leads together to reduce the cable loop area. On the alternating current side, it is possible to reduce the cable length of the protective earth, phase and neutral conductors by twisting them together so as to avoid unnecessarily large cable loops in the system. The metal oxide varistor is probably the most popular clamping device used for transient suppression.

Finally, going off-grid requires an appropriate mindset. The relevant standards are evolving to keep up with ambitious home owners, but for the installers working on these jobs, creating a fully-functional off-grid installation requires proper administration and maintenance scheduling.

But then, with the electrical side sorted, the next hurdle is figuring out how to stay fed. Time to brush up on pickling, preserving or befriending someone with a very productive veggie patch.

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT