UNSW researchers achieve world-record efficiency for emerging antimony chalcogenide solar cells

Photovoltaic researchers at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) have achieved the highest independently verified efficiency ever recorded for solar cells made from antimony chalcogenide, an emerging material tipped as a strong contender for next-generation solar technology.

The UNSW engineering team has demonstrated a certified power conversion efficiency of 10.7%, a world-first result for the material. The findings, published in Nature Energy, mark a major step forward in efforts to develop solar panels that are cheaper, more efficient and more durable.

ADVERTISEMENT

The breakthrough has earned antimony chalcogenide its first inclusion in the international Solar Cell Efficiency Tables, which track record-setting photovoltaic results worldwide.

Beyond the efficiency milestone, the researchers say they have identified the fundamental chemical mechanism limiting the material’s performance, opening the door to faster progress in future development.

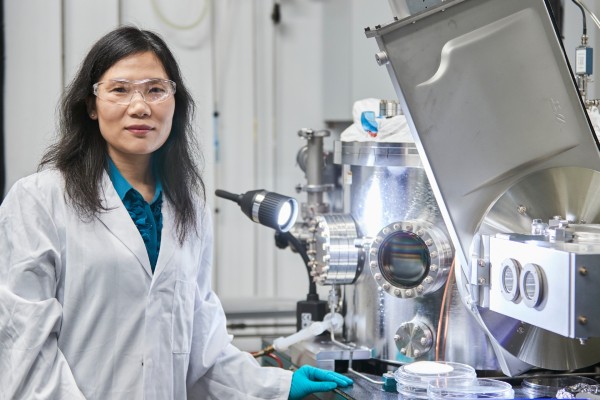

Professor Xiaojing Hao, from UNSW’s School of Photovoltaic and Renewable Energy Engineering, says the work is particularly significant in the context of tandem solar cells, where multiple layers are stacked to capture more of the solar spectrum.

“The next generation of technology for solar panels is tandem cells, where two or more solar cells are stacked on top of each other. What researchers around the world are trying to work out is what material is best to use as the top cell in partnership with a traditional silicon cell,” Professor Xiaojing says.

“We need more top cell candidates that can partner with silicon. Antimony chalcogenide is one of those and very positive, especially given its distinct properties.”

Antimony chalcogenide offers several advantages over other emerging solar materials. It is made from abundant, low-cost elements, is fully inorganic and therefore more stable over time and has a high light absorption coefficient, meaning a layer just 300 nanometres thick can effectively harvest sunlight. The material can also be deposited at low temperatures, reducing manufacturing energy use and supporting scalable, low-cost production.

Despite these benefits, efficiencies for antimony chalcogenide solar cells had stalled below 10% since 2020. The UNSW team discovered this was due to an uneven distribution of sulfur and selenium during production, which created an energy barrier that hindered the movement of electrical charge through the cell.

Dr Chen Qian says the effect was similar to forcing electricity to move uphill: “It was like driving a car up a steep slope. When the distribution of the elements inside the cell is more even, the charge can move more easily through the absorber rather than being trapped, which means more sunlight is converted into electricity.”

The researchers found that adding a small amount of sodium sulfide during the hydrothermal deposition process stabilised the chemical reactions and improved the internal structure of the material. In laboratory testing, the cells reached an efficiency of 11.02%, with CSIRO independently certifying a result of 10.7%.

The team says further gains are likely through defect reduction using chemical passivation techniques, with a near-term target of reaching 12% efficiency.

Beyond tandem solar panels, antimony chalcogenide also shows promise for other applications. Its ultrathin, semi-transparent properties and high bifaciality make it suitable for solar windows, while its strong performance under indoor lighting could support devices such as smart badges, sensors, e-paper displays and internet-connected devices. A UNSW spinout company, Sydney Solar, is already working to commercialise window-based solar stickers.

“In the next few years we will continue to work on reducing the defects in this material via passivation. We believe increasing efficiency to 12% in the near future is achievable by addressing the remaining challenges step by step,” Dr Chen says.

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT