Generation ‘Why’: The next stage of apprentice evolution

Times have changed since the average reader of Electrical Connection finished their apprenticeship. For example, these days Justin Bieber is considered a good singer and Twilight is seen as a good movie.

It’s shameful, really.

ADVERTISEMENT

Even since I left school 12 years ago the electrical industry has changed dramatically, and the attitude, nature and needs of apprentices entering the market have changed alongside it. And to ensure the future growth and development of the industry it is up to you, as potential employers, to keep abreast of these changes.

Recently, the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER) for Electrotechnology and Telecommunications Trades Workers, and industry skills council E-Oz Energy Skills Australia, released a paper examining the changing landscape of electrical apprenticeships in Australia.

KEY FINDINGS

The paper, titled The changing face of electrical apprentice training, found that today’s electrical apprentices are, on average, older with more life experience.

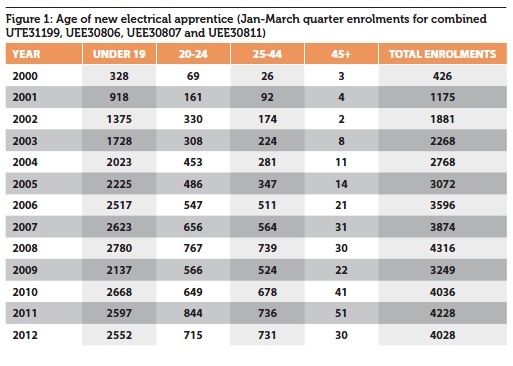

The average age of apprentices commencing their formal training has increased since 2000.

The proportion of students under 19, while still the largest group, has diminished by about 14%. This represents a 60% increase in the proportion of new apprentices above the age of 19, a trend that is expected to continue (see Figure 1).

Between 2007 and 2011, the number of electrical apprentices in Australia grew at an average annual rate of over 6%. But, while the total number of electrical apprentices has continued to grow strongly, the growth in new apprenticeships began to slow considerably from 2007, suggesting that future growth is not guaranteed (see Figure 2).

This dip in apprenticeship commencements, which coincided with the global financial crisis, will ultimately lead to a reduced number of qualified tradespeople entering the industry this year, exacerbating skills shortages as economic growth picks up (see Figure 3).

COMPLETION

Perhaps the most concerning trend to be identified, though, is the falling number of apprenticeship completions over the past few years. While the number of electrical apprentices has grown, individual completion rates (the main indicator of how many electricians are entering the industry) has fallen by 10% in five years (see Figure 4).

E-Oz stakeholder engagement team leader Juan Maddock suggests this is because the industry is attracting the wrong people into apprenticeship positions.

“The government’s 2010 expert panel on apprenticeship reform identified high-quality recruitment as the most important factor in apprenticeship completions,” he says. This can be achieved in three ways:

> The occupation – “Some apprentices get a year in and simply decide this is not what they want to do for the rest of their lives. This is a waste for all parties (employer, apprentice and government who funds the training) and can be best addressed by giving apprentices more information upfront so that they make an informed choice.”

> The employer – “The most common reason cited by apprentices for not completing is that they don’t get on well with their employer. This can best be addressed through the recruitment process and by talking through problems with apprentices when they arise.”

> The training program – “Unlike higher education programs which have entrance requirements; RTOs are required to take all apprentice candidates that have an employer. Some of these apprentices are simply not prepared to undertake the training program, particularly in relation to numeracy.”

“E-Oz’ data shows that apprentices that don’t have the literacy and numeracy levels recommended to undertake a unit are three times more likely to not complete. In fact, surveys of RTO trainers indicate that almost 50% of apprentice non-completions are related to inadequate numeracy skills,” Juan says.

“Part of this is related to advice provided in secondary schools, where trade training is promoted to students struggling academically. There needs to be better recognition that being an electrician requires high level mathematical skills. If students are serious about the profession, they should study maths through to year 12.

“This problem is being compounded by an increase in university enrolments. In 2006, COAG set a target for increasing the proportion of 25-34 year olds with a university degree from 30% to 40%. This has resulted in a huge jump in university enrolments, with many students who would have undertaken a trade apprenticeship going to university instead.” Research on the reasons for leaving an apprenticeship conducted in 2009 by NCVER and the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), combined with feedback from MEGT’s Group Training operation, showed electrical apprentices:

> Didn’t have the maturity to understand and think through what they were getting into;

> Experienced financial difficulties;

> Were distracted by life experiences;

> Thought the grass is greener in a different industry or employer;

> Thought the job didn’t turn out to be what they had originally expected; and,

> Thought expectations of their employer are too high for them.

“Let’s look at their world for a moment. It’s usually their first job and they have left the supportive environment of school to the brand new environment of the workplace. It is a totally different protocol for dress and behaviour,” MEGT group marketing manager Linda Nall says.

“They have money for the first time, so they can buy a car now and they can easily overextend themselves if they don’t have financial advice (advice they will listen to and respect). Their friendship group has changed – so they are trying to establish new bonds in the workplace. And they don’t want to look stupid by asking what they think may be perceived as being dumb questions.”

As such, many apprentices will simply wander off for reasons you don’t see as being important.

“Losing a good employee costs money in re-recruitment and training time. Losing an apprentice before they have finished their qualification, unless it is a planned strategy to work-share them, undoes all the time you invested so far,” Linda says.

So, after all the effort you’ve gone to advertise and recruit, after all the time you’ve taken to bring them up to speed, how are you going to hang onto them?

“Most tradespeople understand the need to employ apprentices: to be able to handle existing as well as future business and to ensure skills are not lost to their industry. And MEGT knows from its surveys of clients that a key motivator in taking on an apprentice is to do the right thing by starting a young person in the industry the employer has chosen as a career.

“So, it’s important to know why they leave so you recognise the signals before they get themselves into a bind.

“Many of them leave for what you and I would see as really unimportant or fixable reasons, but because they either don’t want to communicate with a parent, or don’t have a parent that understands what they are going through, or don’t have anyone in the workplace to confide in, they can make decisions without understanding the impact it will have on their life.”

The Group Training model of employment was established in 1981 to assist in providing apprentices with continuity of employment so they could complete their apprenticeship, and mentoring is integral to that service. However, for direct-employed apprentices, the lack of a mentor was identified as a necessity.

Last year, the government made available free mentoring support for apprentices that may not have access to support. This mentoring support is available to Australian apprentices and trainees who: > Are working for an employer with up to 50 employees (nationally);

> Are aged 16–19 years (inclusive);

> Don’t have assistance from anywhere else;

> Are undertaking a qualification on the National Skills Needs List;

> Are not employed by a Group Training Organisation;

> Are registered through MEGT Australian Apprenticeships Centre; or,

> You believe would benefit from contact with a mentor.

COMPETENCY

Another approach to improving completion rates is the recent introduction of competency-based training (CBT). CBT describes a series of workplace tasks at which an individual must demonstrate ‘competence’ (i.e. operating at the standard identified by industry as required in a workplace) in order to complete it. Each task is allocated to a Competency Standard Unit (CSU), which are then grouped into qualifications.

The standards themselves are set by panels of industry experts at a national level, rather than by educators within training institutions. This means that a qualification like the Certificate III in Electrotechnology Electrician – the electrical apprenticeship – is the same right around the country and is designed to meet the needs of industry.

The North Melbourne Institute of TAFE (NMIT) was recently selected to trial the new electrical apprenticeship program in 2013, offering individuals the chance to complete their apprenticeship when deemed competent. Candidates who enter the national Managing Apprenticeship Program (MAP) pilot program will receive significant benefits, including an assigned industry mentor to help them stay on track with apprenticeship requirements, and be placed on an industry register for employer selection.

“While CBT has been in place since the 1990s, efforts are now being made to shift to competency-based progression (CBP) with COAG targets to this effect,” Juan says.

“The main difference is that CBP allows students to learn at different rates based on their individual skills and knowledge rather than in ‘lock step’ with the rest of the class.

“This is not about accelerated progression but about tailoring a training plan to the needs of the individual. This has benefits for the training organisation, employer and apprentice because, in any particular unit, the apprentices that need extra help (i.e. might fail otherwise) are given extra support and apprentices who quickly gain the skills and knowledge are able to move ahead (and aren’t held back by the struggling apprentices).”

To work, training institutions need to be able to manage a class of apprentices each at a different stage in their progression. This requires a new set of skills for the training as well as resources for apprentices to undertake self-paced learning.

They must also be able to offer ‘assessment on demand’, with assessments taking place when the apprentice is ready rather than for the whole class at once. Upon its launch, the move to CBT received support from the peak Australian electrical industry body, the National Electrical and Communications Association (NECA).

Chief executive James Tinslay says, “NECA acknowledges that many in the industry feel that four years is the minimum that an apprenticeship should be served but this pilot would accommodate those apprentices that are able to demonstrate competencies prior to the traditional four year completion rate and also those who would benefit from additional time served.”

He says the program is not about watering down the requirements but rather strengthening the electrical apprenticeship training program.

“This program allows flexibility both ways with the focus being on safety and quality of skills application.”

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT